grief.

I was going to write about cheese this week, but instead, I’m going to write about mammograms. Classic pivot, right? I feel like grief has caused a lot of these pivots in my life. I go like an innocent fool to a Lone Bellow concert to enjoy the music of my favorite band, and end up sobbing into Will’s chest, my back to the stage, during half the songs because they all remind me of my mom. (Something about a stripped down “Watch Over Us” and the lyrics “You’ve had your time, but who has tomorrow?” *sob*) Or I go like an innocent fool to someone’s wedding hoping to have a good time and ending up sobbing into Will’s chest and spilling a whole glass of red wine down the back of his white shirt on the dance floor (true story) because I can’t be happy for the life of me and seeing everyone smile makes me miss her too much. Or I go like an innocent fool to the Palace Market in Point Reyes for water buffalo ice cream with my friend Pam and end up sobbing in the granola bar aisle in front of a row of Luna bars because my mom always used to pack the Chocolate Peppermint Stick one in my lunches in high school and just having them in my eye line makes me weep. (It tastes like a candy cane, highly recommend.) If grief is anything, it’s a sneaky motherfucker. It has no face, and it has every face.

This week, I was lucky enough to go to my fifth mammogram of my thirty-three-year-old life. Because my mom was first diagnosed with breast cancer at thirty-five, I’ve been getting them every year or so since I was twenty-seven. (The rule of thumb for descendants is ten years before the original diagnosis, but I think I started a year or two after that. If anyone this applies to is interested in getting more info about this or talking it through, let me know!) Because young women’s breast tissue is particularly dense, the mammograms are sometimes only marginally helpful, so my doctor suggested I get an MRI every other year, which is more invasive but can be more effective, and switch off with the mammograms. A never ending mammogram-MRI sandwich, yay! (Thank you, THANK you, insurance.)

So, a year ago, I had my first breast MRI. I was nervous the entire week leading up to it. Early detection is the best way to increase odds of survival, so I felt good about my decision to get the MRI. I’ve been trying my best to give myself every chance of a positive outcome if I do end up getting breast cancer. 1-in-8 women get breast cancer unless you have someone in your family with it, and then your chances become about 1-in-4. My mom did not have the BRCA gene, which would increase those odds further, so that is one good thing. The odds are still in my favor, but a huge swirl of anxiety surrounds all heath-related issues for me, particularly those related to cancer.

The day after the MRI when I was supposed to get the results, I could barely move my body. Everything felt slow. I couldn’t concentrate for more than thirty seconds at a time. This happens to me sometimes. I get into freeze mode and basically lay on my back all day. It’s called dorsal vagal shutdown. I try to distract myself until it becomes an acceptable hour to go to bed and then I fall asleep. It really sucks. I tried to talk myself through it. The odds are really low something showed up on the MRI. Your life is not going to be your mom’s. You’re going to be let off the hook and get on with your life and go eat some mac and cheese and feel silly you were so worried. This is just a routine check up. (I have to tell you, even typing this all out now, my body is reacting, and I feel the heaviness in my chest as though I’m about to shut down. Again, that body-mind connection. It’s no joke. A writer with anxiety, constantly trying to render the most traumatic moments of her life in words over and over—there’s a word for that, right?)

And then, at around 4:49 pm the day after the MRI, as though I had manifested it, I got the call that no one wants to get. “We don’t know anything for sure, but something suspicious showed up on your scan.” (Disclosure: I’m TOTALLY fine, it ended up being nothing to worry about at all.) But, of course, I freaked the fuck out, my whole body flushed cold, my face on fire. I was told the next step was to get an ultrasound on my breast so we could get a closer look at what the suspicious thing might be, but the earliest they could get me in was Tuesday. Which, yes, you’re right, meant I HAD TO WAIT THE WHOLE FREAKING WEEKEND TO FIND OUT IF I WAS DYING.

After I hung up with my gynecologist who had delivered the news, I sobbed into Will’s chest. (Are you picking up on a pattern here? Lots of snotty t-shirts in our household.) We went for a walk with Mudbug to Laurelhurst Park and everything looked so green. What if I die from cancer and don’t get to see trees ever again, I wondered. What if Will has to live the rest of his life without me? What if the rest of my short life is chemotherapy and hospitals? What if I die without ever having been a mom?

I’m sure this is a common response to this type of news, no matter what your history with cancer is. Any bad health news is scary. But my reaction was also fueled by a little thing called health anxiety, which since my mom’s death, I now have. It’s “an obsessive and irrational worry about having a serious medical condition.” Kind of hypochondriac-esque but more complicated than that. It shows up in many different ways.

For me, for example, a few years ago, I requested an x-ray on my back, against my doctor’s advice, because I felt a bit of pain at the top of my spine and because my mom’s cancer had spread to her back. I was convinced cancer was coming to get me just like it had gotten her. The day the results were supposed to come back, I went to see a movie by myself in the middle of the afternoon so that I would be forced to concentrate on something and couldn’t look at my phone obsessively. When the movie ended, I had a voicemail. “You have a small amount of arthritis in one vertebra, but it’s nothing to worry about,” my doctor said. “You’re going to live a very long life.” Not sure where she got that information from, but okay!

Whenever I’m overly fatigued, I start to wonder if it’s because I have a serious condition I don’t yet know about. (This was mostly before COVID. Now every time I’m tired, I worry I have COVID, but everyone worries about that, right?)

I’m scared each time I see my dad’s name flash on my phone because he was the one who always called with the bad news about my mom, and my body remembers that, a wave of nerves swimming up my stomach when his name appears.

Whenever my dad goes in for a routine procedure of some kind, I can’t fully start my day until I know that the results are. My mind instantly shuffles through a highlight reel of worst case scenarios I can’t shake.

It can show up like this for me, too: Having watched my mom die, the trauma of that, I sometimes think I see the look of death in Mudbug’s eyes, that moment when someone goes from alive to dead. Sometimes, when Mudbug is daydreaming, her eyes stock still, her beautiful green eyes on the verge of sleep but not yet closed, not blinking, she looks as though she could very well no longer be breathing, and I watch her belly to see if she inhales, my own breath caught the whole time. When she was a puppy and separated herself from Will and me, going into the other room to nap, I’d stop our TV show every twenty minutes to make sure she wasn’t dead. So far, she never has been. But when the rules about death no longer apply to you, it could come at any minute. My mom was never supposed to die, not in the summer after college, not on a beautiful Wednesday afternoon in June, not when I still had so many questions to ask her, not at all. And yet.

Why couldn’t the dog be dead in the other room?

My anxiety in general has ballooned since my mom died, like one of those pill-sized capsules you put in water as a kid that transformed into a full foam dinosaur by the end. You know what I’m talking about, right? It was small and contained before and now it is big and has strange, fuzzy edges and soaks up everything it touches.

Some of this might sound really intense or disruptive to you (or maybe not!), but I’ve come to learn it’s a natural response to such a big, uncontrollable change in my life. It’s my mind and body trying to protect me because they think I’m under attack, that I need to be hyper-vigilant now that I’ve lost my defenses. It can be annoying and stressful and, sometimes, it gets in the way of my life, but I’m doing my best to roll with the punches and to find ways to calm myself in certain situations the best I can.

In her book Anxiety: The Missing Stage of Grief (A Revolutionary Approach to Understanding and Healing the Impact of Loss), Claire Bidwell Smith, a grief expert, writer, and therapist, writes about this exact thing. I haven’t read the entire book yet, but what I have read has been extremely helpful and validating. (Claire seems awesome in general. Follow her on Insta if you want to learn more! She also wrote The Rules of Inheritance about losing both of her parents when she was young, which is a great book.)

When asked in an interview how grief and anxiety are related, Claire said, “When some big change comes seemingly out of nowhere and disrupts life, we realize we're not safe, things aren't certain, we're not in control. All of that is true all of the time, but loss is a huge reminder. The life changes and emotional upheaval are so much bigger than most people understand. Grief, which is the series of emotions that accompany a significant loss, can drop you to your knees. That feeds anxiety.

Grieving people can begin feeling anxious about their own health or the safety of other loved ones. Sometimes, they don't even realize what they are experiencing is anxiety or is in any way related to their grief.

Anxiety, a psychological condition that causes fear and worry, can present with many physical symptoms. These can be misleading, making you think you have heart palpitations, a stomach issue, a new sweating problem, headaches, insomnia. Many people think they have a medical problem and not an emotional one.”

When I got my scary MRI news last year, I luckily already had a hiking trip planned with two of my dear friends, Becky and Pam, and their partners near Port Townsend, Washington. It fell on a day between when I received the news and when I was going to get the ultrasound, those scary, unsure hours when I pictured over and over again what my life would look like as a thirty-two-year-old with breast cancer. A choose-your-own-adventure story, and on Tuesday my choice would be made for me. I got to talk with Pam and Becky for hours about how I was feeling and what it would mean if the ultrasound came back showing cancer. I’d seen the way cancer had taken over and ended my mom’s life. Why wouldn’t my story be the same?

Pam and Becky assured me that a lot of the technology had improved since my mom had first gotten diagnosed, that it would be so early, my chances would be incredibly good, that so many people get breast cancer and survive for a really long time. All true.

I will never forget those hours I spent walking with Pam and Becky and then the additional two hours I sat with Pam, who has taken on a mother role for me since my mom’s death, on a stoop in a Port Townsend parking lot, her husband, Mike, listening gently on, as she laid out for me how things might go, as she told me, in her deep down self, she didn’t think it was going to be bad news. I trust Pam’s deep down self more than almost anything, so this made me feel hopeful.

And maybe the biggest soother of all, the thing that made me feel safest, is the knowledge that I would have Pam and Becky there again to go through it with if it came down to it. And Will. And my incredible dad, sister, brother, and Kay. My friends Laura and Sarah who hand delivered me lunch the day after the MRI results phone call. And everyone else who loves me. I saw it happen for my mom. I saw how her people gave her strength and love, the way they gathered around her with late night visits or shopping trips or phone calls or by making dinner or coming over for lunch. I don’t know how we do anything without our people.

I made it to Tuesday. I had the earliest appointment available that morning, and was at the breast clinic early. When the technician started the ultrasound, moving the little wand thingy over my boob, I craned my neck, until it hurt, to see what she was seeing on the screen. Like I would know anything about what I was looking at. Moving swirls of gray and white and black. Some of them looked like cancer to me, but then again, some didn’t. I was told the radiologist would be the one to decipher the images for me once the technician had finished, but I had to ask her. “What do you see?” The technician told me I’d need to wait, which I knew meant she’d seen cancer. She left the room when she’d gotten what she needed, my heart like a rabbit’s thumping foot, and when the radiologist walked in the room four years later, she sat next to me.

“It’s a lymph node,” she said and stopped.

…

…!

…!!

WHAT DOES THAT MEAN?!

“What does that mean?” I said. “Do I have cancer?”

“You do not have cancer,” she said. “It’s perfectly normal. MRIs pick these up a good percentage of the time.”

“So, you’re sure I don’t have cancer?”

“I’m sure,” she said, and reader? My body instantly dropped seventy-five pounds.

I asked more questions—I am an incessant question asker in these scenarios, give me ~*all the info*~—, and she said a lot of words in Latin or something, and when I gave her a little layup by saying, “I’m so glad I don’t have cancer,” wanting a third confirmation, just to be sure, she said, “I am too. You’re free to go.” And I went!

Like the universe sometimes throws you lay ups itself, Will and I already had a getaway planned since he had the week off work, and we were leaving in a few hours. (After I called Pam and texted Becky and Laura and my family and everyone else I’d told, the relief in their voices buoying me more.) I’d found a cute little cabin on a vineyard in Oregon wine country, and we were going to taste some wine and eat good food and explore a new part of our adopted state. So I got to celebrate all weekend the fact I wasn’t dying. (Or, more accurately, as someone who is always dying. From one of my favorite Annie Dillard quotes: “Write as if you are dying. At the same time, assume you write for an audience consisting of solely terminal ill patients. That is, after all, the case.”)

Will and Muddy and I walked around the vineyard. (Well, Muddy sprinted through the vines.)

We met Scottish highland cows, and ate ice cream sandwiches with rainbow sprinkles that are still somehow crushed into the seams of our car’s passenger seat. (Wasn’t me 😏 ). We drank whiskey and watched Cats. (omg…there is not enough whiskey in the world…) And I felt like I got a second shot at it all, the world brighter and full of more possibility and color and grace. I wasn’t going to die from cancer. At least not right then. For the first time, I started to believe that maybe my mom’s life really wasn’t going to be my own. I learned a lot from those five scary days—about fear and safety and my priorities. About changing the story in my head that tells me all the time the news will never be good.

An FYI: My dad’s partner, Kay, when I called my dad and her to tell them about the suspicious scan, had mentioned what I’m about to explain. But I had gotten my COVID vaccine about four or five weeks before I got the MRI. The lymph node on the MRI showed up on the same side I got my shot. No one asked me when I was scheduling my appointment when I had gotten my most recent COVID shot. If they had, they would have suggested I wait at least six weeks to schedule my MRI. My immune system was more flared up, and this could be why the lymph node appeared on the MRI. When I scheduled my 2022 mammogram a few weeks ago (which came back normal, btw), they did ask me this question. It’s been shown COVID vaccines can affect these types of scans (MRIs, mammograms, etc.), so beware! You may not always be asked about that when you’re scheduling. I could have been saved a lot of angst if those dots had been connected for me earlier.

I do want to mention that, along these lines, there is a school of thought about these types of early screenings that urge against mammograms and MRIs (or at least yearly ones) because of this exact thing—they are fallible and can cause more harm/anxiety/money than is necessary. That they can actually do more damage for a person’s overall wellbeing because of these false positives and the invasiveness of some of the procedures. And also because there are so many different kinds of breast cancer. Some that would never metastasize enough to be harmful. Some that are so aggressive that by the time a mammogram takes place, the cancer has already spread. Sometimes, positive mammograms for certain cancers lead to other procedures or radiation that end up being unnecessary and put the patient at risk for other side effects. I understand this way of thinking, and it’s up to each person to decide how they want to handle their health. The best we can do, I think, is gather our research and information and make the most informed decision for us at each step along the way.

Also, of course, something I kept thinking throughout this experience is how very lucky I was to even have access to this type of prevention, to have the insurance and money and infrastructure and support to choose this option. That was another thing that kept me lifted throughout those five days.

All this to say, if your anxiety and stress have blossomed since a death or major change in your life (or if you have anxiety for any reason at all), if the world feels unsafe because of these big shifts, if your body seems to work against you, or your mind feels sometimes like it’s sabotaging you, I see you, and I hear you. Grief gives you all kinds of things—crying in supermarkets and strange cravings and, sometimes, surreal clarity. It also rearranges how you function, how your systems learn to survive. There is nothing wrong with you. These are completely expected and natural responses, no matter how confusing or frustrating they may sometimes be. There are ways to cope and manage, and I’ll share some of them on the GOOD / GRIEF Instagram page. (Speaking of—please follow GOOD / GRIEF on Instagram if you haven’t already! I’m still working on ramping up what I post there, but I’m hoping to include more writing and resources as the weeks go on. I think it will be a cool way to build this community further.)

Now, enough about cancer! Time for some happier things!

good.

First off, I wanted to share that a short story of mine was published this month in an awesome literary journal called Colorado Review. This is one of the first pieces of fiction I ever tried writing. I wrote the first draft about four years ago, and I’ve spent the time since revising and revising and revising again based on feedback from my writing groups, so it’s cool for me to see it in its final form in the world. It’s about grief (duh), and while we’re on the wine theme, it takes place on a vineyard in South Africa! You can read the story here.

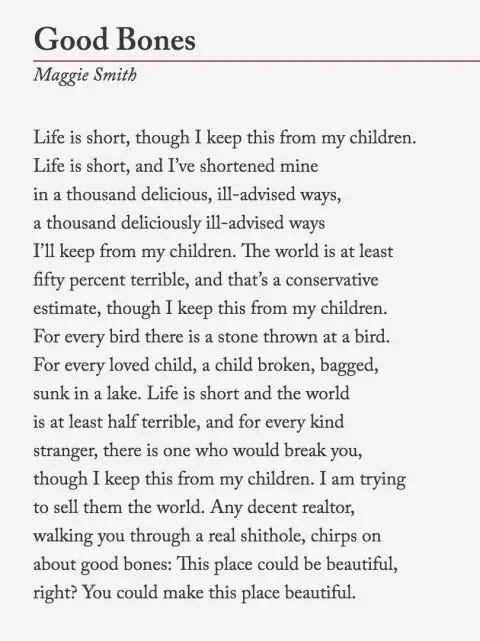

Next, if you and I have spoken more than twice, I’ve probably sent you this poem “Good Bones” by Maggie Smith because it is one of my favorite pieces of writing ever. Or maybe you’ve already read it elsewhere because it’s just so amazing. But it encompasses much of what I hope to touch on in this newsletter, the way life can be devastating and hopeful in the exact same breath. I leave you with this gorgeous poem from Maggie’s book, also called Good Bones.

Eyes up, everyone. There could be good news ahead. :)

x / o,

(the other) Maggie

Maggie! Reading this as I am in the midst of learning Didion’s Year of Magical Thinking is revelatory. She separates herself in weird ways that you helped me understand better.

My Mom and her family heritage (possibly that generation) sent such strong messages: don’t TALK about it; oh, it’s nothing… I had that too and it was nothing; don’t be dramatic (to a young aspiring actor!! ) Basically, it was ‘stick your head in the sand and pretend it isn’t there.

You are soooo gifted as a writer and friend: you can express yourself mightily and you have good people surrounding you who hold you up. It is so admirable.

I also love how we all negotiate with the possible outcomes. I have almost never had a mammo w/o being sent in for ultrasound. Everything you described around the first and second. And then my doc one time describing the spot she went in after on my right breast as ‘ A Hunk of Junk’. Now, at 70, my mantra has become: if I go get it checked out right away, it will be nothing. If I wait, it will be something. My choice. Luckily, even the little stuff has been just that. Little.

Didion tried so hard to control it all. That’s a really hard road I think. I’m glad to be the actor and get to share it with whoever wants to walk thru it with me. That’s what you have created for yourself. Miss smarty pants I would say :) love A